This article was originally posted on AmericanBanker.com and you can read it here.

By Penny Crosman August 30, 2021, 2:24 p.m. EDT6 Min Read

When American Banker made predictions more than a year ago about what banking would look like in 2025, one of them was that it will be “invisible” — in other words, embedded in other things people do and places they go, with banks unseen in the background.

In embedded banking, customers can obtain a financial product or service from a company or website that has nothing to do with finance, such as a store, a doctor’s office or a vacation rental site.

In some ways this trend has taken hold faster than expected: Many retailers have begun to offer buy now/pay later loans with the help of banks and fintechs behind the scenes. Late last week Amazon announced it will offer such loans through Affirm which, in turn, works with lenders Cross River Bank and Celtic Bank. Several financial institutions — including Citigroup, Seattle Bank and Sound Federal Credit Union in Connecticut (formerly Stamford Federal Credit Union) — have agreed to offer bank accounts through Google Pay. Goldman Sachs offers a digital credit card through Apple.

In an interview earlier this year, Stephanie Cohen, global co-head of consumer and wealth management at Goldman, said one of its main strategies “is to be a platform — taking our capabilities and embedding them in the ecosystems of our partners. The idea is to take our banking technology platform that we’ve built and embed it into other ecosystems in a multiproduct way.”

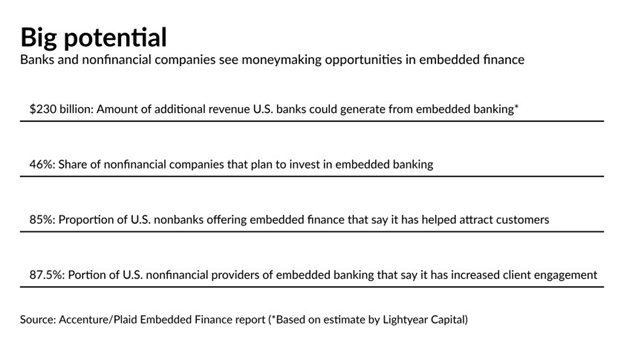

More U.S. banks of all sizes are seeing the value of extending services through third parties to broaden their customer bases, develop new revenue sources in the form of fees from the third parties and to stay relevant as big tech and fintechs offer consumers high-concept apps. The New York private equity firm Lightyear Capital has estimated that banks that capitalize on this trend could reap $230 billion in net new revenue by 2025.

The concept

Zac Townsend, associate partner at McKinsey & Co., defines embedded banking simply as “nonfinancial services players somehow bringing finance into their experience.”

Townsend points to the banks working with Google, Goldman Sachs’s work with Apple and Amazon, and Walmart’s venture with Ribbit Capital as examples. McDonald’s loyalty app could lead to the fast-food chain becoming a payment provider and getting further into banking, he said.

“If the last five years are really about fintech companies proving that they can do deals with banks, I think now you’re going to see a wave of bigger corporations — retailers, tech companies, insurance companies — start to do it,” Townsend said.

E-commerce was a natural place for one type of embedded banking to start out: the recent rash of buy now/pay later loans now available on most shopping websites. But embedded banking won’t be a fit everywhere, Townsend cautions.

“It doesn’t make any natural sense for me to have 50 bank accounts across a whole wide spectrum of different services,” he said. “But if I was a small business, I think it could make sense for my bank accounts to be offered by my payroll provider or my accounting software. If I own a restaurant, my restaurant management software could be a natural place to embed my payroll or embed financing on my receivables. For big corporates, enterprise resource planning software is a natural home for some of their cash management. For cross-border finance, you can see natural homes in travel apps or TripAdvisor.”

Brad Leimer, co-founder of the venture capital and consulting firm Unconventional Ventures, defines embedded finance as putting a portion of banking inside the business model of something outside of banking. In some cases, there might be a “super app” in the center, like the one PayPal is developing.

“PayPal started as a payment application, then it acquired Braintree and Venmo, and continued down that path,” he said. “They continue to grow out this idea of a financial super app.”

Pieces of banking might get embedded in Uber, Airbnb and other popular apps, Leimer said.

“You used to only be able to offer banking products if you were a bank,” he said. “Now you’re seeing Starbucks, retail apps and lifestyle apps” offer pieces of financial products.

Big retailers like Walmart and Amazon will be at the center of this, Leimer predicts. “If you think about what Amazon does, it’s doing everything it can to try to get you to stay and shop,” he said. “What’s to stop them from offering other types of banking services?”

Smaller retailers, and even dentists, doctors and lawyers could all be part of embedded banking, Leimer said. They might use banking data and services for credit assessments or identity checks, or to offer buy now/pay later loans. A community bank might allow a local health care client to offer credit to its customers.

“Why couldn’t a smaller institution leverage the tools that they have to offer credit services, identity checks, insurance services, wealth management, all these other things through their merchant partners that are already clients, some of which are pretty sizable?” Leimer said.

TAB Bank’s next stop

TAB Bank in Ogden, Utah, was founded 23 years ago as an affiliate of a chain of truck stops, providing financing and payment technology to truckers on the road, said CEO Curt Queyrouze. It set up kiosks in the truck stops so a driver could drop off a load, take the bill of lading to the kiosk and fax it to the bank, which would give the trucker credit to pay for fuel, tires or whatever might be needed.

“We were doing mobile banking before the smartphone existed,” Queyrouze said. The bank has never had a branch.

In 2009, the truck stop chain the $1.3 billion-asset bank had partnered with went bankrupt.

“We lost that connection, so we had to rebuild our suite of services outside of that connection,” Queyrouze said. “That’s when we started embracing fintechs.”

TAB Bank now works with MuleSoft in San Francisco for its application programming interfaces and Provo, Utah-based MX for data management. It makes small-business loans through SmartBiz, a website that matches borrowers with Small Business Administration lenders. It also works with six other marketplace lenders, some of which offer buy now/pay later loans through retail sites.

All of this is preparation for the bank’s plan to offer embedded banking.

“We see embedded finance as the future we’re chasing,” Queyrouze said. “We believe that all of what we’re doing today will eventually be done closer to the point of transaction. We want to provide these services when and where and how the customer needs them. Ultimately, we believe that will be a place where the customer would not even be thinking about the bank or the enterprise that’s providing the services. It will happen seamlessly in the background.”

The pathway to that future is unknown. “So we’re navigating what we believe is an eventual, logical move towards embedded everything that will be driven by customer expectations and technology companies,” Queyrouze said. “It’s up to the industry to figure out how to play in that new world.”

Third-party risk

When a bank extends its services through a third party, it takes on the risk that the partner might do something to sully the bank’s reputation, fall prey to a cybersecurity snafu or suffer a breakdown in customer service.

“You’re basically extending your brand,” Leimer said. “But the question is, would the consumer even know?” Regulators may at some point step in and set rules around embedded banking, he said.

Queyrouze pointed out another risk of working with fintechs like marketplace lenders: “The business model is a little more volatile, and you have to have to be very aware of that and take that into account when you’re building the bank of the future.”

For instance, TAB Bank netted $7 million in revenue from its work with marketplace lenders in 2020. In 2021 it’s on track to reach $17 million. But Queyrouze recognizes that that number could also fall sharply in the future.

A team at TAB analyzes legal, reputational, marketing, compliance and accounting risks of any new partner.

“It’s not a stable, annuity type of income stream that we’re used to in banking,” Queyrouze said. “We’re trying to be careful about how we build out these income streams and not become overly reliant on a handful.”

Executive Editor, Technology At American Banker And Arizent, American Banker